Introduction

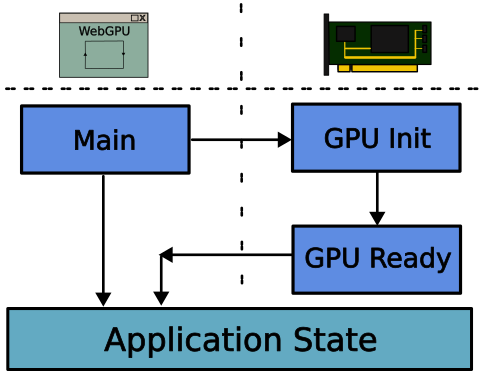

The context in WebGPU is much more complicated than in WebGL; but have no fear we will soon dispel this. Recall, in the first part, that the WebGL Context is simply a case of a single function call. WebGPU allows much more flexibility, and this is it’s power. It allows us to control the GPU device, its command queue, and the states that connect them explicitly. So, without further ado, let’s get to it.

Application State

First thing is to create a place to store objects that allow our application to run. This is called the application state, we discuss this briefly in the previous part; our main struct called *Application*. Several of the objects in the state are Options, because they are initialised asynchronously on in response to lifecycle events. This is the full structure here, we will go through it bit-by-bit:

pub struct Application<'w> {

proxy: EventLoopProxy<AppEvent>,

gpu_ctx: Option<GpuCtx>,

window: Option<Arc<Window>>,

surface: Option<Arc<wgpu::Surface<'w>>>,

surface_config: Option<wgpu::SurfaceConfiguration>,

}The first object in the state is the EventLoopProxy which is a proxy to the main event loop. It is customised to handled our own events, specified in AppEvent, which we will return to later. When we create the Application, later, it will take control of the EventLoop, which is the main code that intercepts and processes loops that our application has to deal with. If we wish to send our custom events, we can only send them to the event loop through this proxy, as we will no longer be able to access the original EventLoop that is owned by the Application.

The second object is a GpuCtx object, which we go through in detail in the next section. In essence, it contains information about our GPU and allows us to interact with it.

The last few objects are connected, they are; window, surface, surface_config. The window is an object that connects to our canvas, and allows us to intercept and manage events like mouse clicks, resizing, and key presses. Connected to that is a surface, and it’s configuration; the surface is our painting surface, and what our WebGPU will render to. This will then update the canvas element via our window.

Window

So, we now know that we need a window to handle events that are related to the canvas, like resizing, closing, key presses and mouse clicks. The window is created through a windowing library; for a desktop application, this would actually create a window; for us we attach it to a canvas element. We create a function to encapsulate all our window creation logic:

fn create_window(&mut self, event_loop: &ActiveEventLoop) -> Arc<Window>The next step is to identify the canvas element in our HTML DOM that we want to attach to. In this tutorial, we gave our canvas a specific id in our index.html, namely “canvas”. We use web_sys to first get our DOM document, and then select the element by this id.

const CANVAS_ID: &str = "canvas";

let web_window = web_sys::window().unwrap();

let document = web_window.document().unwrap();

let canvas = document.get_element_by_id(CANVAS_ID).unwrap();

let html_canvas = canvas.unchecked_into::<web_sys::HtmlCanvasElement>();Finally, we create the window inside an Arc (so we can share it later). To do this we need to specify what attributes it needs to have. For our purposes, we just use the default, and pass in our canvas element. The window is returned from our function.

let attrs = Window::default_attributes().with_canvas(Some(html_canvas));

Arc::new(event_loop.create_window(attrs).unwrap())When to create the window

Now we have our function to create our window, we need to add it to our code at the appropriate time to call it. This time is when the application resumes, which is called at the start of our application, and any time that we refocus on our application after having moved away (switching tab, for example). This function is part of our ApplicationHandler described in the last part, and it is called resumed.

First things first, we check whether or not the window has been initialised and added to our state; if not we call our create function:

if self.window.is_none() {

let window = self.create_window(event_loop);

self.window = Some(window);

}We should now create our surface in this function using the window, but first we must cover the GPU Context, which we need to create it.

GPU Context

Our GPU Context is the structure that contains all the objects we need to communicate with, and control the GPU through WebGPU. It has the following structure:

pub struct GpuCtx {

instance: Arc<wgpu::Instance>,

adapter: wgpu::Adapter,

device: wgpu::Device,

queue: wgpu::Queue,

}The GpuCtx must be initialised asynchronously to avoid blocking the browser and causing it to hang. We therefore put all of our code in a single asynchronous function, that we use to request an initialisation. Inside this function we will create our instance, request our adapter and request our device. We will show how to call this properly later, but for now we need to understand that it will asynchronously initialise these objects, and then signal back to our application that it is ready through a custom application event.

impl GpuCtx {

pub async fn request(event_loop_proxy: EventLoopProxy<AppEvent>) {

...

}

}Instance

The instance is the starting point of WebGPU; it represents the instance of WebGPU itself. From it, we will request the parts of the system that we need in later parts. We don’t need much for the instance, but to simply request what backend we want to use. This we specify by filling in the InstanceDescriptor structure, and passing it to the new function. Here we request the WebGPU backend.

let instance = wgpu::Instance::new(&wgpu::InstanceDescriptor { backends: wgpu::Backends::BROWSER_WEBGPU });Adapter

The adapter represents a concrete physical (or virtual) GPU chosen by the WebGPU instance that satisfies our requested constraints. It only has a few options:

- The

power_preferencedescribes whether you want a low power device, a performance device, or you don’t care. - The

compatible_surfaceis just there to request an adapter that is compatible with the surface we need to render on (seems important). - The

force_fallback_adaptertells the request whether or not you are happy with the fallback (software normally) implementation.

let adapter = instance

.request_adapter(&wgpu::RequestAdapterOptions {

power_preference: wgpu::PowerPreference::default(),

compatible_surface: None,

force_fallback_adapter: false,

})

.await

.expect("Adapter not found");Device

Now we have our adapter, we can finally request from it a device that matches out capabilities. This call also gives us our queue. We use the queue to send our device some commands to perform. For now, we use just some default values:

let (device, queue) = adapter

.request_device(&wgpu::DeviceDescriptor::default())

.await

.expect("Device not found");Finishing up

Now we have all the pieces to construct our GpuCtx and signal the Application that we are ready.

let gpu_ctx = Self {

instance: instance,

adapter: adapter,

device: device,

queue: queue,

};

event_loop_proxy.send_event(AppEvent::GpuReady(Box::new(gpu_ctx)));The final piece is then to catch the event, and update our application state, so we can use the GpuCtx later. This is done through the user_event function in our ApplicationHandler, and simply waits for the event to fire, collects the result, and updates our state.

fn user_event(&mut self, _event_loop: &ActiveEventLoop, event: AppEvent) {

match event {

AppEvent::GpuReady(gpu_ctx) => {

self.gpu_ctx = Some(*gpu_ctx);

}

}

}Surface

We can now return to resumed function, and use our GpuCtx to create our surface for rendering. This code follows directly on from our code snippet above, where we created the window.

Firstly, we need to check that the gpu_ctx has been initialized, and we do this by unpacking a reference to the variable:

if let Some(gpu_ctx) = self.gpu_ctx.as_ref() {

...

}Inside this guard, we first create a surface object that is linked to our window:

let surface = Arc::new(

gpu_ctx

.instance

.create_surface(self.window.as_ref().unwrap().clone())

.expect("surface"),

);Next, we must configure the surface, and this takes several steps.

Surface Capabilities

We first get the list of surface capabilities that are supported by our adapter.

let caps = surface.get_capabilities(&adapter);Surface Format

Next, we use the size of the window to create our surface. For everything else, we use very default values. This is not necessarily the best way to do it, as it is not a very customised configuration. However, later in the tutorial we may tweak this section, and our understanding of the rest of the pipeline deepens. One key thing to note, at this point, is this is a RENDER_ATTACHMENT, which means it is a surface used to store the final image for rendering; the texture that the swapchain presents.

let size = self.window.as_ref().unwrap().inner_size();

let config = wgpu::SurfaceConfiguration {

usage: wgpu::TextureUsages::RENDER_ATTACHMENT,

format: caps.formats[0],

width: size.width.max(1),

height: size.height.max(1),

present_mode: caps.present_modes[0],

alpha_mode: caps.alpha_modes[0],

view_formats: vec![],

desired_maximum_frame_latency: 2,

};Bringing it all together

Now, we can finally bring everything together and complete our routine to initialise our window, surface, and GPU context. We modify our Application initialisation code from the previous part with a few additions as well:

let proxy = event_loop.create_proxy();

let mut app = Application::new(proxy.clone());

let gpu_ctx_proxy = proxy.clone();

wasm_bindgen_futures::spawn_local(async move {

GpuCtx::request(gpu_ctx_proxy).await;

});Previously, our Application constructor did not require a proxy to the event loop. Here, we have modify that, so we pass in a clone of the proxy to the new function of our Application. Second, we create a new clone of that to pass to our GpuCtx initialiser (recall it needs it to send an event). As the GpuCtx request function is asynchronous, we must call it from another thread; a blocking call to it would defeat the point of it being asynchronous. Here, we schedule an asynchronous task on the browser’s event loop, that then calls our request function asynchronously and performs the actions as above.

Conclusion

In this part we have covered a lot of ground. This is the beginning of our foray into WebGPU proper. Our application has now been set-up to initialise our GPUCtx, by requesting our instance, adapter, device and queue; all the components we need to issue commands to WebGPU. This has been attached to our canvas through a surface, and our window. Finally, this has been achieved in a multi-threaded way that does not block our browser, or cause it to hang.